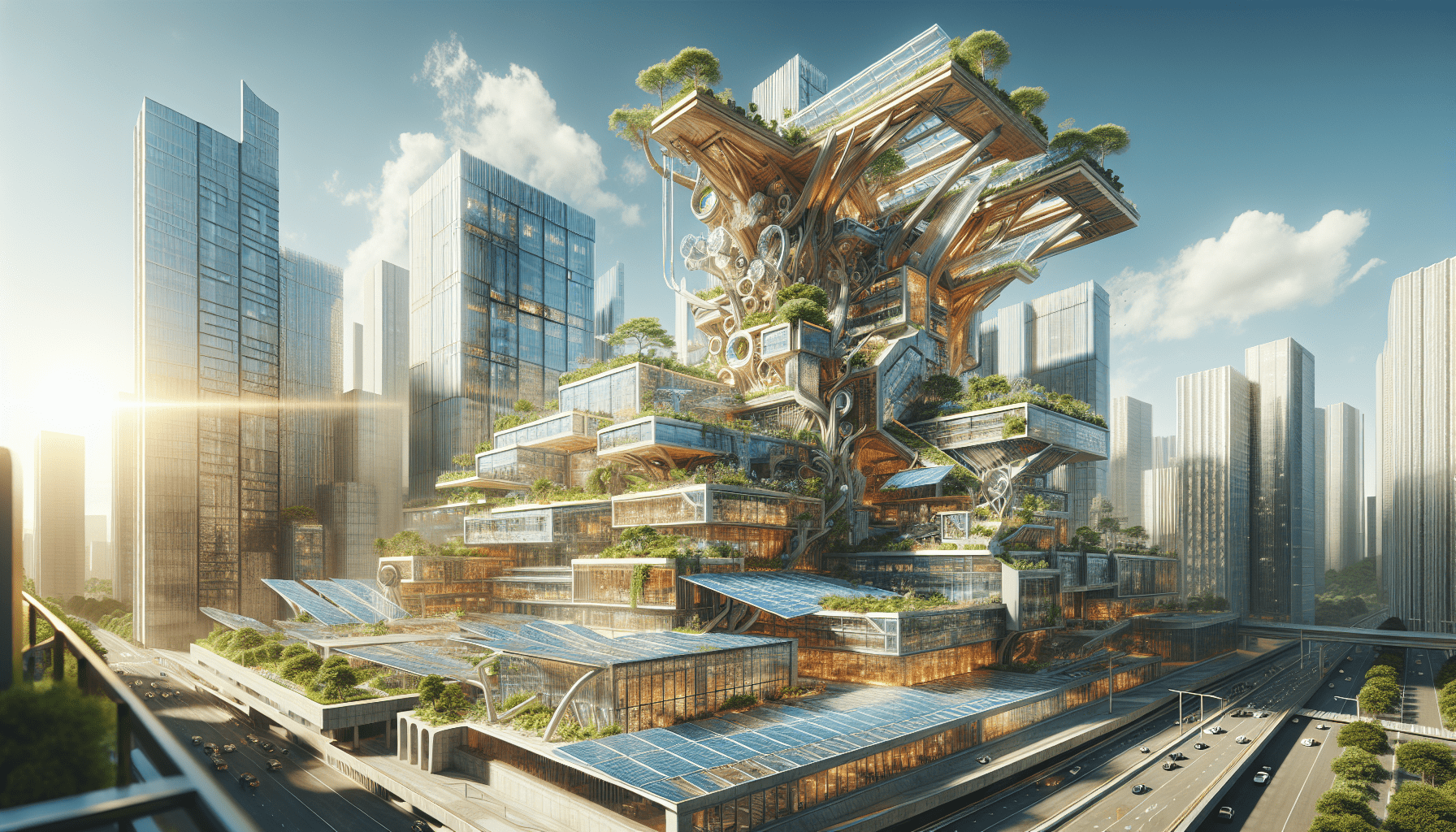

In “What Are The Challenges Of Sustainable Architecture?”, we explore the multifaceted hurdles faced by architects striving to create environmentally-friendly buildings. Together, let’s delve into the intricacies of sustainable design, from balancing innovative technology with traditional practices to navigating complex regulatory landscapes. Our collective journey will shed light on how these challenges can be addressed, propelling us toward a more sustainable future in architecture. Have you ever wondered what it takes to make a building not just beautiful or functional, but also environmentally friendly? As our global population grows and we face the rapid depletion of natural resources, sustainable architecture is emerging as a critical part of the solution. However, designing and constructing such buildings is easier said than done. Today, we’ll explore the challenges faced by sustainable architecture and why it’s a path worth pursuing.

What Is Sustainable Architecture?

Before diving into the challenges, let’s first understand what sustainable architecture entails. Sustainable architecture aims to minimize the negative environmental impact of buildings through efficient use of resources and spaces. It’s a holistic approach that considers the entire life cycle of a building, from material sourcing to longevity and eventual demolition.

Key Aspects of Sustainable Architecture

- Energy Efficiency

- Solar panels

- Natural lighting

- Insulation

- Resource Conservation

- Recycled materials

- Water conservation systems

- Sustainable sourcing of raw materials

- Healthy Indoor Environment

- Non-toxic materials

- Natural ventilation

- Organic interiors

These elements are just the tip of the iceberg. Sustainable architecture encompasses far more complexities, and with complexities come challenges.

Economic Challenges

Initial Costs

One of the biggest hurdles in sustainable architecture is the initial cost. Green technologies and sustainable materials often come with a higher price tag. The financial outlay for implementing solar panels, geothermal heating systems, or even high-efficiency insulation can be substantial. This can be a deterrent for developers and builders who may favor traditional building methods due to cost considerations.

Return on Investment (ROI)

The ROI on sustainable architecture can be slow, adding another layer of financial concern. While energy savings and reduced operating costs can offset initial expenses over time, the upfront costs can make it difficult for some stakeholders to commit.

Financial Incentives

Government grants, rebates, and tax incentives can make sustainable architecture more economically feasible. However, the availability and extent of these incentives vary significantly by region and political climate, making it challenging to rely on them.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Costs | High upfront expenses for sustainable technology | Financial planning, phased implementation |

| ROI | Slow return on investment | Long-term financial planning, life-cycle costing |

| Financial Incentives | Variability in government support | Advocacy for policy changes, diversified funding |

Technological Challenges

Availability of Sustainable Materials

While there’s growing innovation in the realm of sustainable materials, they’re not always readily available. Many regions lack access to these advanced resources, limiting the feasibility of sustainable architecture in those areas.

Technological Limitations

Even with advancements in technology, there are still limitations. For instance, renewable energy technologies like solar and wind power are subject to the inconsistencies of weather conditions, making it challenging to rely solely on them for a building’s energy needs.

Integration Complexities

Combining various sustainable technologies into a cohesive system can be complicated. Every building is unique, and what works for one might not work for another. Designing a system that integrates solar panels, rainwater harvesting, and geothermal heating can be a complex task requiring specialized knowledge and experience.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Availability of Materials | Limited access to sustainable materials | Investment in supply chain, local sourcing |

| Technological Limitations | Weather and climate-based challenges | Hybrid energy systems, adaptive technologies |

| Integration Complexities | Difficulty in combining different technologies | Skilled labor, comprehensive planning |

Regulatory Challenges

Building Codes and Standards

Sustainable architecture can often be at odds with local building codes and standards. In many places, building regulations haven’t caught up with the advancements in green technology, causing friction when trying to implement innovative solutions.

Zoning Laws

Zoning laws can restrict the implementation of sustainable practices. For instance, local zoning regulations may not permit the construction of wind turbines or large solar panel installations, thereby limiting the scope of sustainable architecture in certain areas.

Certification Ambiguities

While certifications like LEED or BREEAM help in standardizing sustainable practices, the processes can be convoluted and expensive. Moreover, the lack of a universal standard makes it challenging to ascertain what constitutes a truly sustainable building.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Building Codes and Standards | Regulations sometimes lag technology | Advocacy, collaboration with regulators |

| Zoning Laws | Local laws that limit sustainable practices | Policy change, community engagement |

| Certification Ambiguities | Complicated and varied certification processes | Streamlined systems, universal standards |

Social Challenges

Public Perception and Awareness

A significant barrier to sustainable architecture is the general public’s lack of awareness or interest. Often, sustainable buildings are perceived as a luxury rather than a necessity. Changing this perception requires widespread educational efforts and advocacy.

Skilled Labor Shortage

There is a noticeable shortage of skilled labor trained specifically in sustainable building practices. This gap can lead to increased costs and longer project timelines, making it even harder to justify the initial investment.

Resistance to Change

Old habits die hard, and many stakeholders in the construction and real estate industries are resistant to change. Convincing them to adopt sustainable practices requires evidence of long-term benefits and possibly interventions like policy changes or incentives.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Public Perception | Lack of awareness or interest | Educational campaigns, media outreach |

| Skilled Labor Shortage | Inadequate number of trained professionals | Training programs, industry partnerships |

| Resistance to Change | Hesitancy from stakeholders to adopt new practices | Pilot projects, showcasing successful examples |

Environmental Challenges

Resource Limitations

Ironically, some sustainable materials themselves are limited resources. For example, bamboo is a popular sustainable material, but it’s not widely grown in all parts of the world, making it less practical for some regions.

Climate Variances

Sustainable architecture must contend with diverse climates and geographical conditions. Designing a building that is environmentally friendly in a temperate climate is different from doing so in a desert or arctic environment. This variability adds an extra layer of complexity.

Waste Management

Even with the best intentions, construction and demolition waste are significant environmental issues. Effective waste management practices are crucial but difficult to implement consistently across all phases of the building lifecycle.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Limitations | Limited availability of some sustainable materials | Local materials, innovative alternatives |

| Climate Variances | Different climates require different solutions | Regional designs, adaptive technologies |

| Waste Management | Significant waste from building processes | Recycling, upcycling, efficient resource planning |

Psychological and Behavioral Challenges

User Acceptance

Regardless of how sustainable a building may be, if the occupants do not use it as intended, its efficiency plummets. Ensuring that users understand and embrace the building’s sustainable features is a challenge in itself.

Behavior Modification

Behavioral changes are essential for maximizing the benefits of sustainable architecture. For example, a building designed to harvest rainwater is only effective if occupants utilize the system correctly, rather than reverting to conventional water consumption habits.

Lifestyle Compatibility

Buildings that challenge existing lifestyle habits might face resistance. For instance, in regions where air conditioning is the norm, convincing occupants to rely on natural ventilation designed into a sustainable building may be challenging.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| User Acceptance | Ensuring occupants use sustainable features | Training, user-friendly design |

| Behavior Modification | Changes in habits necessary for efficiency | Awareness programs, smart systems |

| Lifestyle Compatibility | Sustainable features conflicting with habits | Gradual transitions, dual-mode systems |

Cultural and Ethical Challenges

Traditional Practices

In regions with strong cultural ties to traditional building methods, introducing sustainable architecture can be seen as foreign or even intrusive. Building buy-in from local communities is crucial for the success of any sustainable project.

Ethical Sourcing

Ensuring that the materials used in sustainable architecture are ethically sourced is another challenge. This entails not just environmental sustainability but also fair labor practices, minimal exploitation, and community-friendly operations.

Inclusivity

Sustainable architecture should be inclusive of a wide demographic. Making these buildings accessible and affordable to lower-income communities ensures that sustainability is a universal benefit rather than a privilege.

| Challenge | Description | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Practices | Strong cultural ties to traditional methods | Community engagement, blend of traditional and modern |

| Ethical Sourcing | Ensuring fair labor and environmental practices | Transparent supply chains, certifications |

| Inclusivity | Making sustainable buildings accessible to all | Government programs, affordable housing designs |

Practical Examples

To illustrate these challenges and solutions, let’s look at a few practical examples.

The Crystal in London

The Crystal building in London is one of the world’s most sustainable buildings. It serves as a model for green building technology, showcasing sustainable energy systems, water-saving systems, and waste management practices. However, the high initial costs and difficulties in obtaining certain sustainable materials posed significant challenges during its construction.

Bosco Verticale in Milan

Bosco Verticale, or “Vertical Forest,” in Milan features skyscrapers with trees and plants integrated into their design. The project faced numerous challenges, including the need for specialized knowledge in both architecture and botany, and the initial costs were steep. However, its success has led to greater public acceptance and awareness of the benefits of sustainable architecture.

One Central Park in Sydney

One Central Park in Sydney incorporates a host of sustainable features, from green walls to an intricate water recycling system. Yet, overcoming zoning laws and gaining the necessary approvals required extensive negotiation and advocacy.

Future Directions

The challenges we’ve discussed are significant, but not insurmountable. As technology advances, societal views evolve, and policies adapt, the future looks promising for sustainable architecture.

Technological Innovations

Emerging technologies like 3D printing with sustainable materials and advancements in organic solar cells promise to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Continued investment in R&D is crucial.

Policy and Advocacy

Stronger policies and greater advocacy can help overcome regulatory and financial challenges. Industry professionals need to collaborate with policymakers to push for regulations that facilitate sustainable practices.

Education and Training

Continued focus on education and training for architects, builders, and the general public is essential for the broad adoption of sustainable practices. Investing in skilled labor can bridge gaps and overcome many of the social and psychological barriers discussed.

Community Engagement

Involving the community in sustainable projects can help alleviate resistance to change and foster greater acceptance. Projects that blend traditional practices with modern sustainable techniques can serve as bridges between the past and the future.

Conclusion

While the journey toward fully sustainable architecture is fraught with challenges, the benefits far outweigh the obstacles. From economic and technological hurdles to social and cultural resistance, each challenge offers an opportunity for growth and innovation. By understanding these challenges and potential solutions, we can work towards a future where sustainable architecture is not just an option, but the norm. Let’s commit ourselves to this crucial endeavor, for the sake of our planet and future generations.